The COVID-19 pandemic showed how useful digital technology could be for schools. But it also showed the limitations of technology in the educational setting. Millions of students were able to attend classes online to avoid spreading the virus. But many students failed to learn by such methods. Their educational progress slowed and in some cases went backwards.

Digital tools and the internet have made it easier for students to access educational resources. However, a large number of schools around the world remain unconnected to the internet. Additionally, digital tools have entered markets that have no official supervision. Such educational products do not require any testing or proof as to their value to schools and learners.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) argues against unsupervised wide use of digital tools and AI in education. A recent UNESCO report says there is little evidence that wide technology use improves learning. The organization says digital educational tools can never replace the human connection of teacher and student.

Audrey Azoulay is UNESCO’s Director General. She says there is a very large divide, or gap, between rich and poor countries when it comes to digital resources. Just 40 percent of primary schools worldwide have access to the internet, she said. Many schools also lack electricity, especially in Africa and Central and Southern Asia. In sub-Saharan Africa, just 32 percent of schools have electricity.

And, internationally, about one-third of students were unable to attend online classes during the pandemic.

“Even if connectivity was universal, it would still be necessary to demonstrate …that digital technology offers real added value in terms of effective learning,” the report says.

Often, technology changes faster than it is possible to study it, the report says. Educational technology products change every three years on average. In Britain, for example, just seven percent of educational technology companies had done studies to judge the effectiveness of their products.

UNESCO also reported that many companies pay for studies on the effectiveness of their own product. These studies are not independent examinations.

Pearson, an education technology company, has a tool called Successmaker for teaching math and reading. Independent studies show the tool has little or negative effectiveness in learning. But the company stands by the results of the private study it paid for. That study found the product very helpful to learning.

UNESCO says such companies need to be better regulated. Azoulay said just 14 percent of countries require data protection in education.

“Student data should not be used either by education technology or advertising technology companies for marketing purposes,” the report says. Yet a study of 163 products found that 89 percent of them gathered student data and sent them to third-party companies, often for advertising purposes. This usually happened without the student or parent knowing, the study said.

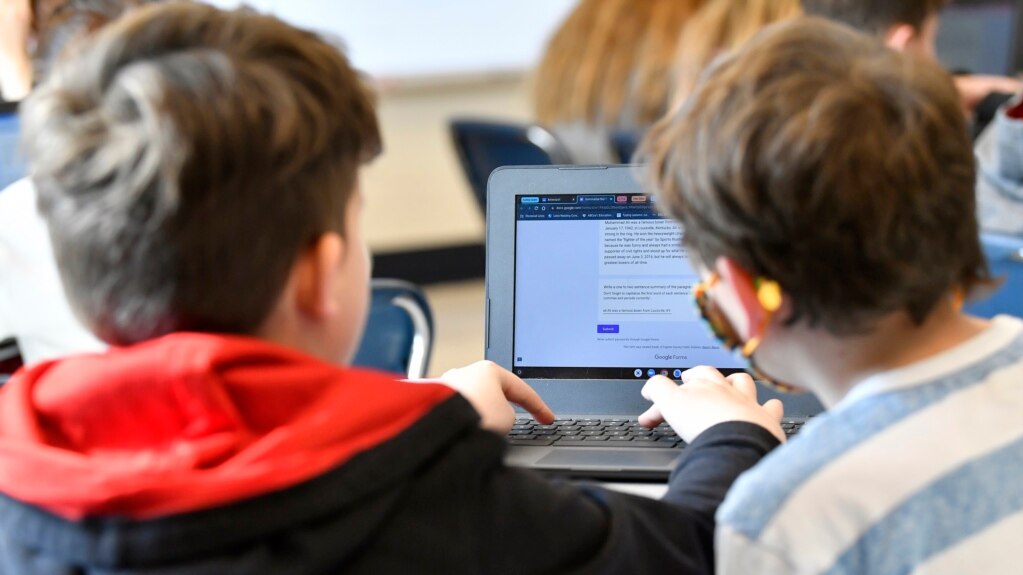

UNESCO argues that technology holds great possibilities for education. But studies have shown that educational technologies are most effective when a teacher is involved in the instructional process.

“We must never forget the social and emotional dimensions of teaching and learning,” Azoulay said, adding, “no screen will ever replace a teacher.”

I’m Dan Novak.