American researchers have combined lab-grown human brain tissue with computer hardware to create a working biocomputer.

The scientists say brain cells used in the experiment were able to recognize speech and complete simple math problems.

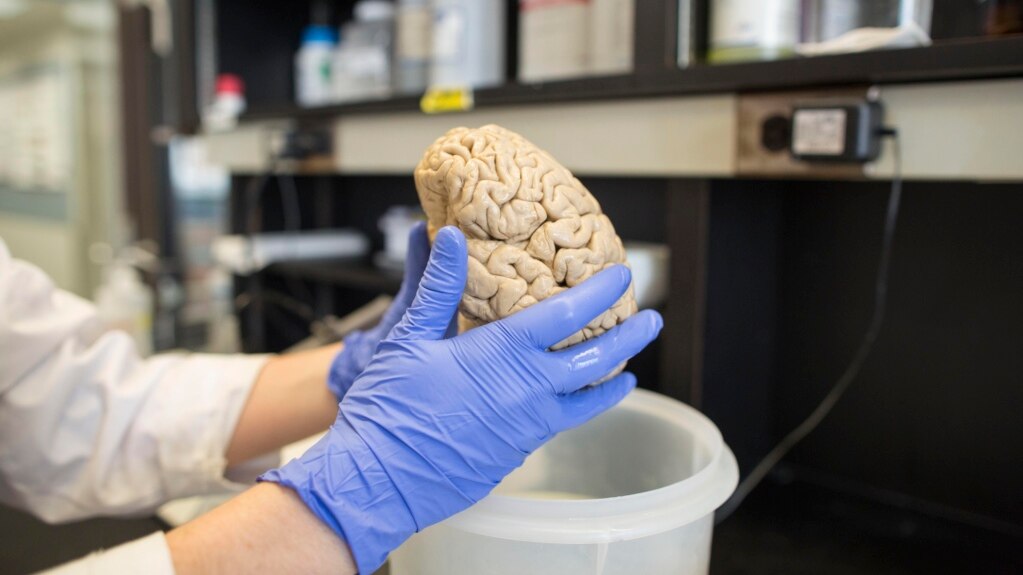

The team made brain-like tissue that took the form of what they called a “brain organoid.” Harvard University’s Stem Cell Institute explains that an organoid is a collection of individualized, complex cells that can be grown from stem cells in a lab.

Under the right laboratory conditions, organoids can be made to look and even work similarly to real human tissue and organs. In this process, stem cells “can follow their own genetic instructions to self-organize,” the Stem Cell Institute says.

So far, scientists have been able to produce organoids that look like, or resemble, some organs. These organs include the brain, kidney, lung, stomach and liver. Such lab-created organoids are generally used to study how organs work without needing to experiment on actual organs.

In the biocomputer experiment, the team said stem cells were able to form neurons similar to those found in the human brain. Neurons are electrically charged cells that transport signals to the brain and other parts of the body.

Feng Guo led the experiment. He is a bioengineer and professor of Intelligent System Engineering at Indiana University Bloomington. His team recently published their research results in a study in Nature Electronics.

The researchers attached the brain organoid to a set of traditional electronic computing circuits. The researchers call this system Brainoware. The system was used to establish communication between the organoid and electronic circuits. An artificial intelligence (AI) tool was used to help read the neural activity of the organoid.

The scientists aim to build “a bridge between AI and organoids,” Guo explained to Nature. Guo believes that combining organoids and computer circuits could provide additional speed and energy to improve the performance of AI computing systems.

The study notes that adding human brain power might be able to help machines with the things they do not do as well as people. For example, the researchers said humans generally have a faster learning ability and use less energy thinking than computers do.

During one part of the experiment, the team tested the Brainoware system’s voice recognition ability. The team trained the system on 240 recordings of eight different voices. The researchers said the organoid produced different neural signals in reaction to the different voices. The accuracy level of the system reached 78 percent, Guo said.

“This is the first demonstration of using brain organoids [for computing],” Guo told MIT Technology Review. He added, “It’s exciting to see the possibilities of organoids for biocomputing in the future.”

Guo said these results persuaded his team that a brain-computer system can work to improve computing performance, especially for some AI jobs. But he noted the best accuracy rates recorded by the Brainoware system were still below the accuracy rates of traditional AI networks. Guo said this is one of the things his team plans to try to improve.

Lena Smirnova is a developmental neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. She told Nature that more research will be needed to improve such systems. But she said, “The study confirms some key theoretical ideas that could eventually make a biological computer possible.”

Smirnova noted that in earlier experiments, researchers have used other kinds of neuron cells to perform similar computational activities. But the latest study, she said, was the first to demonstrate this kind of performance in a brain organoid.

I’m Bryan Lynn.