When teachers at one of the top public schools in Florida are asked how they succeed, one answer is universal: They have autonomy in the classroom.

Teachers with autonomy are able to make decisions and plans independently in their classrooms.

The majority of American teachers report feeling stressed and unhappy at work, a Pew Research Center study found last year. Another study by Brown University and the University of Albany found that reduced job satisfaction has been connected to a drop in teachers’ sense of autonomy in the classroom.

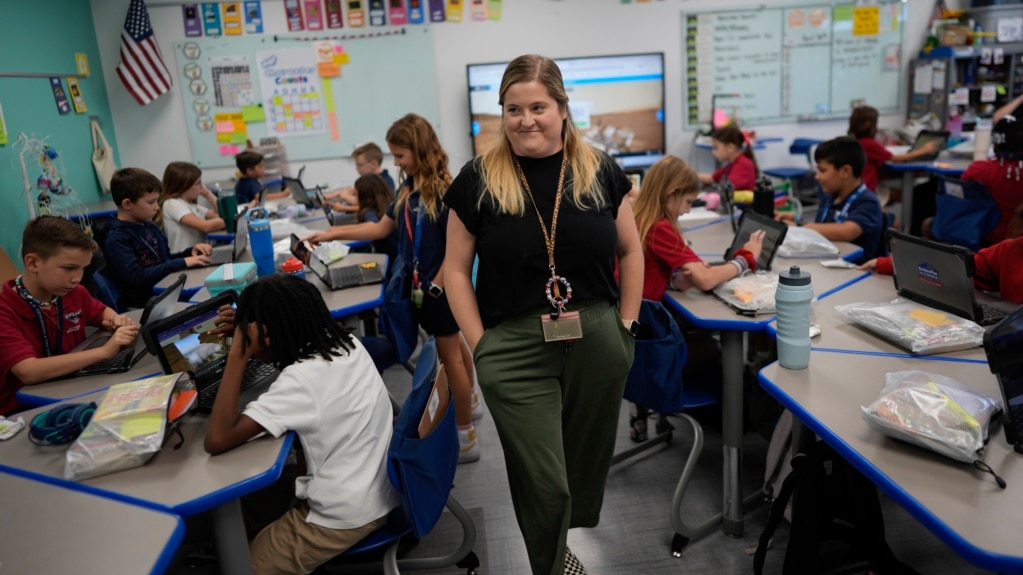

But at A.D. Henderson School in Boca Raton, Florida, school leaders permit their staff high levels of classroom autonomy — and it works.

Henderson is a public school of 636 kindergartners to eighth graders on the campus of Florida Atlantic University. Henderson students scored in the top 1 percent to 3 percent in nearly every subject in the state's latest standardized tests. In almost every subject, 60 percent or more of Henderson students scored far above the Florida state average.

“There is a lot of our own individual input allowed in doing the activities that we want to do in the classroom,” said Vanessa Stevenson. She is a middle school science teacher at Henderson. She plans to start a horse medicine class next fall even though the school has no horses. She believes she will find a way to make the class a success.

“It’s a bit of trial and error because there’s nothing being handed to you saying, ‘Do it this way.’ You just have to figure it out,” she said.

Joel Herbst is the superintendent of Henderson and its partner FAU High School. He called the teachers his “secret sauce.” He said the school’s success can be done anywhere if administrators give teachers more freedom.

When that happens, he said, teachers create hands-on programs that help students learn more.

“Give (teachers) the freedom to do what they do best, which is to impart knowledge, to teach beyond the textbook,” Herbst said.

Madhu Narayanan is an education professor at Portland State University. He studies teacher independence. He said independence is highly related to teacher morale and success. But independence must be combined with administrative support.

“It can’t be, ‘Here is the classroom, here is the textbook, we’ll see you in six months.’ Those teachers have tremendous autonomy, but feel lost,” he said.

About 2,700 families enter a lottery each year for the 60 spots in Henderson’s kindergarten class and openings in other grades.

Some children entering Henderson are gifted. Some have learning disabilities. Most are average learners, however.

The school must follow a Florida law requiring the student population at university-run “laboratory” schools match state population demographics for race, gender and income. Because families apply to attend, parental involvement is high.

Jenny O’Sullivan teaches a class on art and technology. Her kindergartners learn computer coding basics by playing a game with a robot. And fourth and fifth graders make videos celebrating Earth Day.

Her new classroom has the newest technology. But she says such classes can be taught anywhere if the teacher is given the ability to be creative.

Amy Miramontes teaches sixth graders a Medical Detectives class. They examine pieces of rabbit muscle under a microscope, using safe chemicals to find what disease each animal had.

Miramontes hopes the class grows students’ interest in medicine. She also hopes her class gives students the knowledge needed in two years when they take the state’s eighth-grade science test.

Using art to teach science

Henderson’s success has led to more money and grants. The middle school’s drone program, for example, recently won a national competition in California.

Henderson’s drone teams have a room to practice flying the devices through an obstacle course, plus flight simulators donated by the local power company. The drone program is a chance to compete while using the physics and aeronautics learned in the classroom, teacher James Nance said.

Eighth grader Anik Sahai is in Stevenson’s science class. He created an app that uses the camera to diagnose diabetic retinopathy. The eye disease is a leading cause of blindness worldwide.

Sahai’s app took first place in the state’s middle school science fair and is being considered for commercial use. The 14-year-old credits his success to his years at Henderson, beginning in the preschool program.

“The teachers here, they’re amazing,” he said. “They’ve been trained on how to get us to the next level.”

I’m Dan Novak.