Scientists have found the genetic root of a disorder that causes intellectual disability. They say the disorder may affect as many as one in 20,000 young people.

Those with the disorder share a number of conditions, which also include short stature, small heads, seizures and low muscle mass, said the researchers. They published their findings in Nature Medicine.

“We were struck by how common this disorder is” when compared with other rare diseases linked to a single gene, said study lead investigator Ernest Turro of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. The researcher say the findings could help doctors in identifying, the disorder.

Charles Billington is a geneticist at the University of Minnesota who works with children. He was not involved in the study. He said doctors sometimes do not correctly diagnose patients with disorders like these because the signs are hard to recognize.

“So certainly this wasn’t something that we necessarily had a name for,” he said.

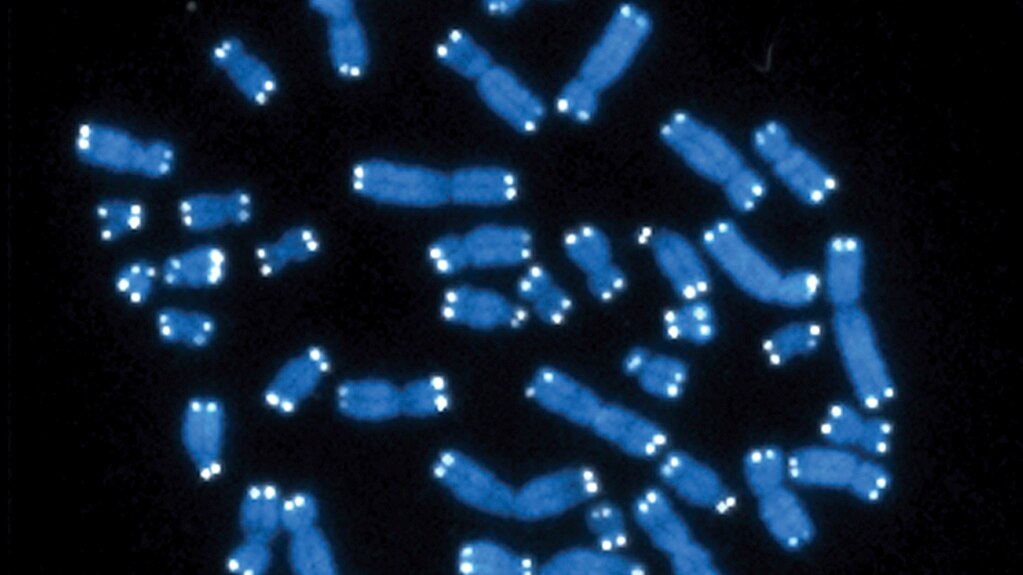

Researchers said the mutations, or changes took place in a “non-coding” gene. Non-coding genes do not provide directions for making proteins. Until now, all but nine of the nearly 1,500 genes known to be linked to intellectual disability are protein-coding genes.

Most large genetic studies use technology that considers only genes that direct protein production.

This study used more complete “whole-genome” data from about 77,000 people who took part in the British government’s 100,000 Genomes Project. About 5,500 had intellectual disability.

The rare mutations researchers found in the gene, called RNU4-2, were strongly associated with the potential for having intellectual disability.

Andrew Mumford is research director of the South West England NHS Genomic Medicine Service. He helped write the study. He said the finding “opens the door to diagnoses” for thousands of families.

More research is needed, Mumford said. How the mutation causes the disorder remains unclear and there is no treatment.

But Billington said laboratories should be able to offer testing for this condition soon. And researchers said families should be able to find and support each other – and know they are not alone.

I’m Gregory Stachel.