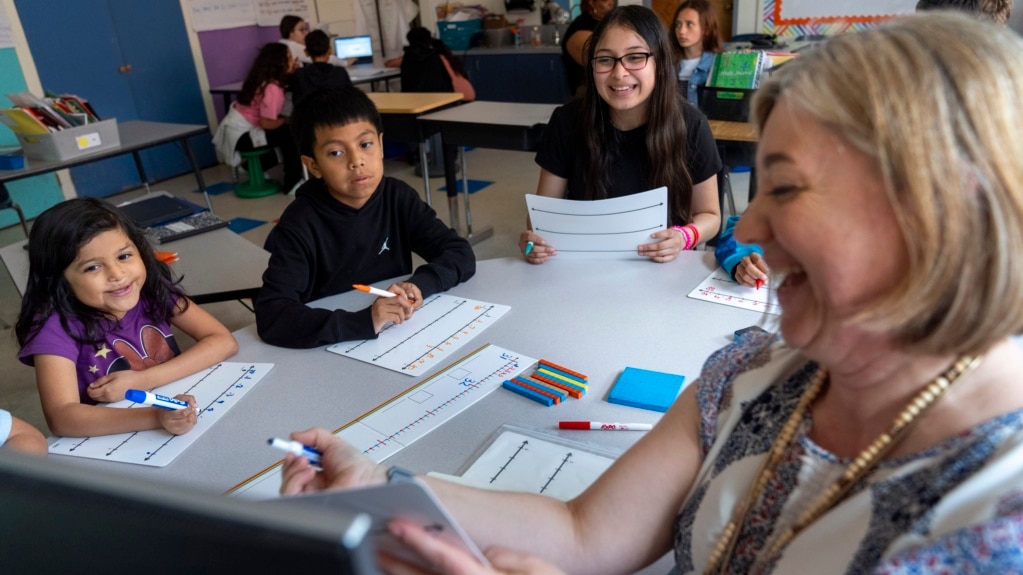

It is a usual school day for third graders at Mount Vernon Community School in Alexandria, Virginia. On one side of the classroom, students surround teacher Maria Fletcher and work on making vowel sounds. On the other side, children read together from a book. In another part of the room, students sit at computers and get reading help from online tutors.

Such activities have become normal for the students. Teachers at Mount Vernon and around the country are racing to get students to learn more, faster. The hope is to get past learning problems that have continued to affect students since schools closed for the COVID-19 pandemic four years ago.

Slow, uneven improvement

America’s schools have started getting back on track. But improvement has been slow and uneven. Millions of students — often poor or from minority groups— are making up little or no progress.

Nationally, students made up one-third of their pandemic losses in math during the past school year and one-quarter of the losses in reading. Those findings come from the Education Recovery Scorecard. That is an examination of state and national test scores by researchers at Harvard University and Stanford University.

But in nine states, including Virginia, reading scores continued to fall during the 2022-2023 school year. And the $190 billion in federal pandemic relief money for schools runs out later this year.

Thomas Kane is a Harvard economist who helped create the scorecard. “The recovery is not finished, and it won’t be finished without state action,” he said. “States need to start planning for what they’re going to do when the federal money runs out in September.”

Virginia lawmakers approved an extra $418 million last year to quicken the recovery. Officials in the state of Massachusetts set aside $3.2 million to provide math tutoring for fourth and eighth grade students who are behind grade level, along with $8 million for reading help. But among other states with slow progress, few said they were spending more to speed up improvement.

In Virginia, the Alexandria school district received $2.3 million in additional state money to expand tutoring.

Ana Marisela Ventura Moreno said her 9-year-old daughter, Sabrina, greatly benefited from extra reading help last year during second grade. But she is still catching up, her mother said.

“She needs to get better. She’s not at the level she should be,” the mother said in Spanish. She noted the school did not offer the tutoring help this year, but she did not know why.

Alexandria education officials say students scoring below proficient receive high-intensity tutoring help. They also said they help students with the greatest needs. Among poorer students at Mount Vernon, just 24 percent scored proficient in math. Just 28 percent of them scored proficient in reading. That is far lower than the rates among wealthier students. And the divide is growing wider.

Failing to get students back on track could have serious effects. The researchers at Harvard and Stanford found communities with higher test scores have higher wages and lower rates of arrest and imprisonment. If pandemic learning losses become permanent, it could follow students for life.

Few recovered to pre-pandemic levels

The Education Recovery Scorecard tracks about 30 states. All of the states saw at least some improvement in math from 2022 to 2023. Nine states saw reading scores drop during that time.

Only a few states have recovered to pre-pandemic testing levels.

In Chicago Public Schools, the average reading score went up by the equivalent of 70 percent of a grade level from 2022 to 2023. Math gains increased less, with students still behind almost half a grade level compared with 2019.

Chicago officials say the improvements were made possible because of the nearly $3 billion in federal relief money. With the funds, the district trained hundreds of people in Chicago to work as tutors. Every school building got an interventionist, an educator who centers on helping struggling students.

The district also used federal money for home visits and expanded arts education.

At Wells Preparatory Elementary on the city's South Side, just 3 percent of students met state reading standards in 2021. Last year, 30 percent met state standards. Federal relief funds permitted the school to hire an interventionist for the first time. Teachers get paid to work on student academic recovery outside working hours.

Vincent Izuegbu is the principal at Wells. He said, “We do not let 10 minutes go by without a teacher giving students the opportunity to engage with the subject.

“That’s very, very important in terms of the growth that we’ve seen,” Izuegbu added.

I’m Dan Novak.

And I'm Caty Weaver.