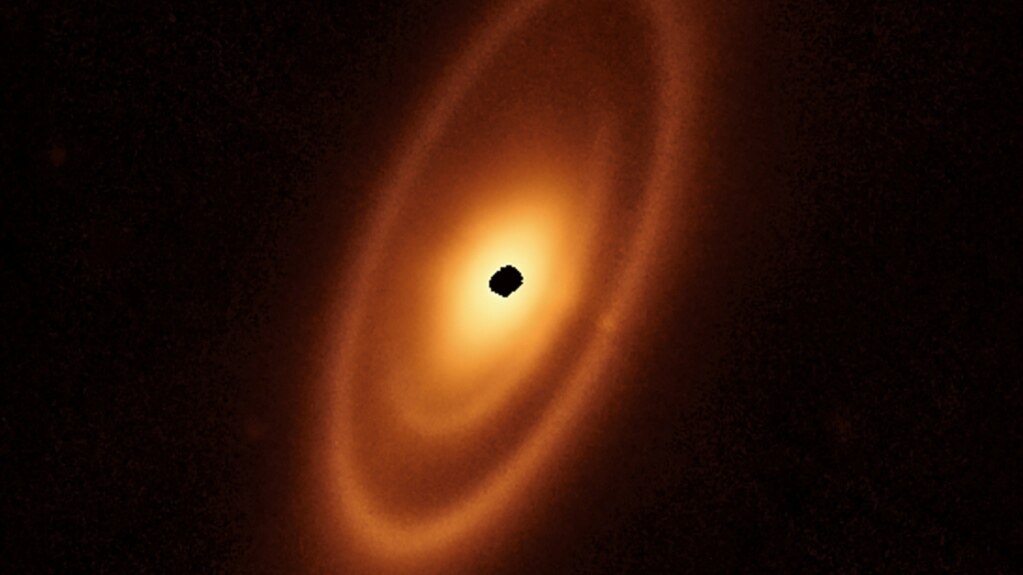

Scientists have released new information about an area around a bright star called Fomalhaut in the Milky Way galaxy. The observations, made by the James Webb Space Telescope, provide details about three rings, or belts, of debris orbiting Fomalhaut.

Fomalhaut, one of the brightest stars in our night sky, is about 25 light years from Earth. A light year is the distance light travels in a year, about 9.5 trillion kilometers.

Researchers first discovered a belt of debris around Fomalhaut in 1983. The Webb found two other rings nearer to the star - a bright inner one and a narrow middle one.

These three belts appear to be populated by solid objects called planetesimals. Some planetesimals are thought to join together early in a star system's history to form planets, while others remain as debris like asteroids and comets.

Andras Gaspar of the University of Arizona was the lead author of the study published in Nature Astronomy.

"Much like our solar system, other planetary systems harbor disks of asteroids and comets - leftover planetesimals from the epoch of planet formation - that continuously grind themselves down” during collisions, he said.

Fomalhaut is 16 times brighter than the sun and almost twice as massive. It is about 440 million years old - less than a tenth the age of the sun - but is probably almost halfway through its life.

The three belts surround Fomalhaut from as far as 23 billion kilometers away. That is about 150 times the distance of Earth to the sun.

While no planets have been discovered yet around Fomalhaut, the researchers suspect the belts were created by gravitational forces of planets. Our solar system has two such belts - the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and the Kuiper belt beyond Neptune.

The gravitational influence of Jupiter, our solar system's largest planet, affects the main asteroid belt. Neptune’s gravitational influence shapes the inner edge of the Kuiper belt.

Gaspar said that observations of Fomalhaut suggest the presence of a huge icy planet in the system.

Debris belts could offer information about planetary beginnings.

"Understanding this formation process requires a complete understanding of how these disks form and evolve," said study co-author Schuyler Wolff.

There are many open questions about the dust in the disks, the scientist added. Debris disks are the remains of a planet formation process, Wolff said, so their structure can provide valuable information about the underlying planet population and history.

I’m John Russell.