At a recent International Energy Agency conference in Paris, government and business leaders said the world is making progress on clean energy projects.

However, the world’s energy demands keep growing. The leaders said there is an “urgent” need for investment in green energy and making better use of already existing energy.

So, how are U.S. universities preparing their students to work on renewable energy projects?

VOA Learning English recently visited with students in the ThinkEnergy Fellowship at Case Western Reserve University’s Great Lakes Energy Institute. The university, known as CWRU, is in Cleveland, Ohio.

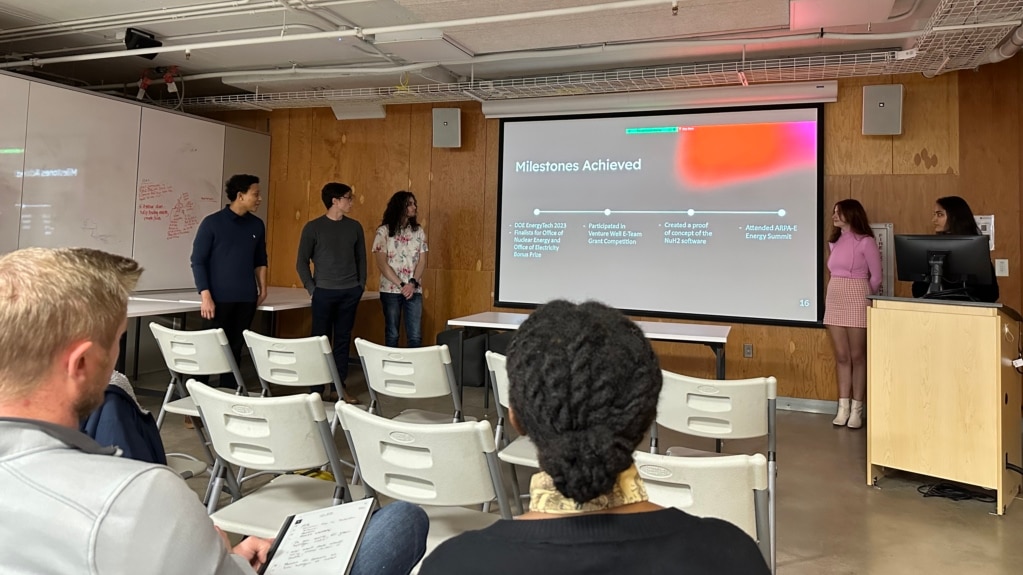

The students spent one year learning from energy experts and working on a final project where they presented an energy business “pitch” to their classmates and advisers.

Students receive money for being in the program, too, up to $10,000 for Ph.D. students. The money helps pay for school but also is supposed to be used as seed money for a business idea.

Who are the students?

The fellowship started in 2015. Each year, the program accepts 10 to 15 students at all stages of their academic careers.

Derin Fasipe is among the fellows. He is working on an advanced degree in biotechnology. He is also working to start a sustainable energy business.

Fellow Molly Egan will soon start her fourth year at CWRU. She studies chemical engineering and has an interest in wind energy.

And, fellow Natasha Rouse recently completed her Ph.D. studies. She will continue working on mechanical engineering, robotics and machine learning projects.

What is the goal of the fellowship?

Jonathan Steirer is the program’s operations manager. He said the goal is for students to “incubate” an idea and turn it into a business.

Non-science students, such as those studying business and arts can also apply.

When students from different academic backgrounds work together, Steirer said, a business student can learn a little about engineering and an engineer can learn about writing a business plan.

At the end of the program, Steirer said, some students find a new study path that leads them to a career in energy.

What projects did the students pitch at the end of the year?

One group proposed a less-costly hydrogen power business called “Nu-H2.” The group looked at “pink” hydrogen power, which is created with the energy that comes from already-existing nuclear power plants.

Another group thought of a small solar-powered engine that could cool the air in a single room. That company is Sol-Air Cooling. Most people live in small homes, so the product could make a big difference.

The third group worked on a solar energy marketplace for homeowners who want to use solar power without costly solar equipment. The group created a website for the marketplace called E-Gora.

Natasha Rouse worked on that project. She saw the business as a chance for average people to make a difference on the climate crisis.

“Frameworks like E-Gora will probably pop up in the next five, 10 years regardless. And those offer people kind of a lower-stakes way into this space. Right, you don't have to spend tens of thousands of dollars to put solar panels on your roof.”

Molly Egan worked on Nu-H2. For many energy projects, “the proof of concept and technology are … right there,” she said. But there are barriers to progress. She said the U.S. electricity grid is outdated as are rules about how to sell and provide electricity.

Are there problems with this kind of fellowship?

There are similar programs at other universities, including Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Columbia University in New York City and the University of Rhode Island.

One engineering school leader likes the “fellowship” model but wonders if it goes far enough.

Ron Harichandran is the leader of the College of Engineering at the University of New Haven in Connecticut. He said most universities in the U.S. do not yet have a “clean energy” field of study. Maybe they should, he said.

He said the world needs major change in the way it produces and uses energy. But he worries that universities “are a little bit scattered” in how they are training students.

Perhaps, he said, mechanical engineers should be working on wind turbine projects. Electrical engineers should be learning how to move solar and wind energy back into the electric grid. Civil engineers should be learning about sustainable building methods and materials.

Harichandran said the fellowship programs are helpful for students who are not completely sure of their interest in energy projects. But there is no guarantee how students might use the money or that they will follow through on their projects.

After all, Harichandran said, the money the programs receive and provide to the students is a gift.

A better way

He suggested the fellowship programs start to think in the same way as some of the large U.S. government organizations that provide financial aid for science.

He mentioned research grants from places such as the Department of Energy, the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) and the National Science Foundation (NSF). They can get strong results because they have clear goals and deadlines.

For example, a research team at CWRU recently won a grant of nearly $1 million from the NSF to work on a sustainable manufacturing project in Ohio.

Fasipe, one of the CWRU students, made similar comments. He said solving the world’s energy and climate change problem is “more complex” than just saying traditional energy production must end. He said costs must come down and businesses need to see that they can make money working in renewable energy.

I’m Dan Friedell. And I’m Faith Pirlo.